International Adoption: An Interview With Jessica O’Dwyer

International adoption is a different journey than domestic adoption. A child has been removed from their birth culture and often brought to homes far from their own and significantly different in customs and culture. Transracial adoption, the joining of racially different parents and children through adoption, can be either domestic or international. A child adopted into a family that looks like they do has a choice about whether they want to tell their adoptive story to people outside the family. When you are a child in a family where you are not the same race as either of your parents, the world notices and often asks questions. The narrative we choose to explain our family’s story is something that we have to decide early on and which, when they are ready, is one that our children should then be allowed to choose.

International adoption comes with its own complexities. For those who choose to embrace the cultural heritage of their children, it adds a rich opportunity to celebrate the customs, traditions, and foods of another country. While it is true our children are growing up in the country in which they are being raised, they have an entire lineage of family somewhere else who are living a culturally different experience. If one day our children should choose to find their biological family it will be beneficial to them to know something of their family’s culture and ideally language.

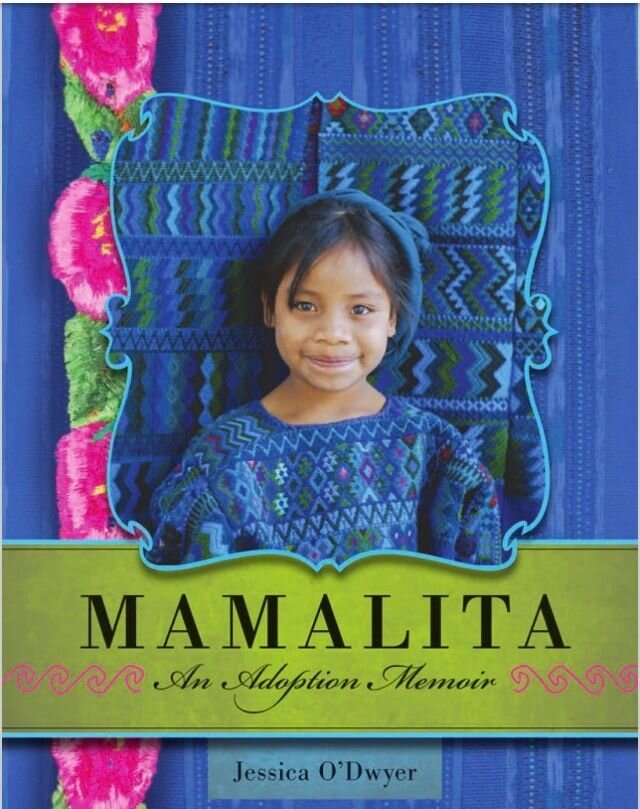

Jessica O’Dwyer is mother to two children adopted from Guatemala and lives in Marin County. She is the author of Mamalita: An Adoption Memoir and hosts the blog: mamalitathebook.com. Jessica’s journey into adoption as it is told in Mamalita is filled with heart-wrenching suspense and insight. A truly fabulous read!

NV: Jessica, thank you for talking with me about transracial-international adoption. I wonder if you could speak about the connection your children have to their birth country, and to their cultural and ethnic identities.

JO’D: Olivia will be sixteen in a few weeks; Mateo is thirteen. Guatemala is an integral part of our lives. Not only my kids’ lives, but also mine and my husband’s. Guatemala is the country we visit every summer. Our home is filled with Guatemalan art and textiles. We keep up with the politics and know the history. We study the language and cook the food. If we hear about a film or YouTube video set in Guatemala, we watch it and discuss. We’re part of a large, active group of adoptive families in the Bay Area. Last year, three girls in our group turned fifteen and celebrated their Quinceañeras together. Our book club reads novels and histories of Guatemala and meets monthly to discuss. We host parties and outings.

Our children identify as Guatemalan and American. Olivia’s family is indigenous, and Olivia specifically identifies as being K’iche’.

Our kids exist in a unique space because they’re part of an adoptive family. They’re Guatemalan, but not “Guatemalan” in the usual way because their parents are white. It’s not so simple. They must navigate their way through many identities, searching for what fits, discovering who they are and where they belong.

NV: How do you believe your decision to return to Guatemala on a regular basis has impacted your children?

JO’D: Guatemala feels very familiar to our children, almost like a second home. Antigua is the place they know best because we rent a house and live there for a month every summer. But we’ve also traveled to many places: Tikal, Livingston, Rio Dulce; Nebaj, Chajul, and the Ixil region; Totonicapán, Quetzaltenango, and Chichicastenango; and the towns around Lake Atitlan—San Juan, Santiago, Panajachel, San Antonio Palopo, San Andres.

Guatemala is a beautiful, fascinating country. I encourage everyone to visit.

NV: You live in a similar area in Marin County to where Flip’s family moved. Could you share your children’s experiences growing up in a place where the people in their schools and church are predominantly white?

JO’D: My children know what it feels like to be “other.” That’s the best way I can describe it. There’s everyone else, and then, there they are. Marin County is regarded as a “liberal” place, but it’s not that different from the rest of the world. Most people are nice, but others—children and adults—have said some nasty, unkind things, or given us looks that can only be described as unfriendly. Some of it’s about race and some is about adoption. And this is everywhere, by the way: in the US and in Guatemala.

In general, we keep the lines of communication open so our kids feel safe telling us about episodes when they happen. We try to help them develop tools and coping mechanisms to deal with situations themselves.

But overall, our lives are circumscribed in the same way most people’s lives are circumscribed. We know everyone in our orbit—at school, at church, in the neighborhood, at the grocery store. And those people are wonderful!

NV I know that you have made it a point to have your children learn Spanish. Can you talk a little bit about why you felt that was important?

JO’D: The first year we went to Latin American Heritage Camp in Colorado, we attended a panel discussion led by young adults who’d been adopted from Central and South America. The audience was filled with adoptive parents and the question was asked, “What’s your advice for us? What’s one thing you’d like us to know?” And to a panelist, each of these young adults said, “Teach your children Spanish. Even if your kids rebel and resist. Keep trying.”

Language is power. It’s the way we connect with one another. You’ve heard the expression: “We speak the same language.” When we go to Guatemala, it’s great to be able to communicate directly with people. Speaking another person’s language often leads to deeper understanding of that person.

What’s interesting is the way my kids’ attitude toward Spanish has evolved. When they were younger, they studied the language because they didn’t have a choice. They took Spanish in school; they studied for a month every summer in Guatemala; and for five years, Olivia attended a two-week Spanish immersion camp in Minnesota (Concordia). All that learning was directed by us, their parents.

But as teenagers, they’re out in the world as independent operators. Because of the way they look, strangers start speaking to them in Spanish. Kids at school who are bilingual speak to them in Spanish. My kids want to speak Spanish if only because everyone assumes they do. To become fluent is their goal now, not mine. And let’s face it, being able to speak another language is totally cool.

NV: Do you have any comments or thoughts about Sliding Into Home as it applies to your experience of how our children relate to their cultural and ethnic heritages growing up in the United States and more specifically Marin?

JO’D: What I loved about your book is the way you captured the complexity of life for our kids. So much of what they encounter and endure is invisible to most Americans. It can be challenging for kids who are adopted, especially when they look different from their parents: Constant questions, constant double-takes, all the time, everywhere they go. And this is around the world, not only Marin.

Lately, when Olivia and I are out together—whether in Marin County or Antigua, Guatemala—she sometimes asks me to walk three steps behind her. Nobody recognizes we’re together, and that’s the way she likes it. She wants to be seen for who she is, outside of her relationship to her parents. She wants to be known as Olivia.

NV Thank you Jessica for taking the time to do this interview. Jessica’s book Mamalita:An Adoption Memoir can be found on Amazon and in bookstores around the Bay. Her blog mamalitathebook.com keeps up with current events in Guatemala and inspires dialogue about issues related to Guatemala.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Are you internationally adopted or are your parents immigrants to the USA?

2. Does having immigrant family or being internationally adopted impact you negatively in any way? Explain.